In 2014, shortly after finishing their fifth consecutive losing season, the Miami Marlins signed their franchise player, right fielder Giancarlo Stanton, to the most lucrative contract in professional sports history, a 13-year, $325 million agreement characterized by backloaded money and a player opt-out following the 2020 season. The sheer dollar amount in conjunction with the notoriously thrifty nature of the Marlins organization made the contract rather notable, and while nobody could argue against Stanton’s desire to earn nearly a third of a billion dollars, there was an inherent drawback for the slugger–playing for the Marlins.

But after just three seasons, Stanton found a reprieve–following a personally successful but mediocre team season, and with his salary about to escalate from $14.5 million to $25 million, the Marlins were looking to shed payroll, and Stanton was looking to play for a winning team. Stanton had a no-trade clause, which he leveraged, proclaiming that he would only waive it to accept a trade to one of the previous season’s four League Championship Series participants. While both the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants reportedly arranged trades with the Marlins that the team found agreeable, Stanton refused to waive his no-trade, and eventually, he was dealt to the New York Yankees.

It is unknown what the Cardinals offered to the Marlins for Stanton, but it was presumably something more appealing than the offer the Marlins eventually accepted–infielder Starlin Castro and two low-level minor leaguers. The return for Stanton, on a purely visceral level, seemed low–Stanton was the defending National League MVP and he had just hit 59 home runs in a season, and Castro had settled into baseball middle age as a good-not-great middle infielder. But the important factor in play was, of course, money–while Castro had two remaining years of salary arbitration (and inevitably below market rate one-year contracts) and Jose Devers and Jorge Guzman would continue to make minor league salaries, Stanton had a massive contract remaining due to him.

Entering 2018, Giancarlo Stanton’s remaining contract was for ten years and $285 million, with a player opt-out after three years and a team option for an 11th year which included a $10 million buyout. Even after Stanton had the best season of his career, this contract still didn’t look like a bargain. And while the Yankees, as much or more than any other team, could afford to set aside $295 million to pay their new designated hitter, this was $295 million they could not use for J.D. Martinez, who instead signed a five-year contract with a lower average annual value with the Yankees’ primary rival and was more than twice as valuable by Wins Above Replacement over the first two years of their tenures with the Yankees and Boston Red Sox.

When Nolan Arenado signed his current contract with the Colorado Rockies, their situation was not nearly as dire as that of the Miami Marlins, but even if he did have the foresight to see the team’s immediate plunge into mediocrity, the Giancarlo Stanton precedent meant that Arenado signing a contract which would make him generationally wealthy was probably the smart move anyway. The new way of baseball is that unless your performance falls apart, other teams will regard your essentially market-rate contract as an asset beyond how they would regard you if they were offering that contract to a free agent. Hence the degree to which Nolan Arenado trade rumors have spiraled beyond the realm of basic logic.

Nolan Arenado, in basic terms, is a good baseball player. He is not, despite what your local St. Louis Cardinals beat reporter may have told you, the best player in the National League, nor is he the third-best player in Major League Baseball, as MLB Network has claimed. At the very least, there is no objective metric to suggest that this is the case. Limiting it to position players only, Nolan Arenado was the 13th best player in Major League Baseball last season by FanGraphs Wins Above Replacement and the 14th best player by Baseball Reference WAR. Over the last two seasons, Arenado ranks 9th and 10th, respectively. Over the last three seasons, 9th and 7th. I’m not entirely sure why it is that Arenado’s accomplishments have been so inflated–his raw power numbers are inflated thanks to playing half of his home games at Coors Field, but the same media that refuses to enshrine the worthy-by-park-neutral-statistics Larry Walker in Cooperstown are the same ones driving home the notion that Arenado is the best defensive third baseman since Brooks Robinson and the best overall third baseman since Mike Schmidt, neither of which complies with reality.

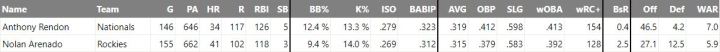

I have a longstanding annoyance with the attention Nolan Arenado receives, and it’s admittedly unfair to him–while being the 14th best position player in baseball (as Steamer projects for 2020) makes one necessarily overrated if the standard line is that he tops all non-Mike Trout players, that still makes him a very good player, which he is. But for the sake of basing thoughts on Nolan Arenado on his actual production rather than the narratives surrounding him, let’s look at his 2019 numbers compared to those of another third baseman who, like Arenado, was scheduled to reach free agency following the 2019 season, but unlike Arenado, didn’t sign an extension and instead tested free agency: Anthony Rendon. Numbers are courtesy of FanGraphs.

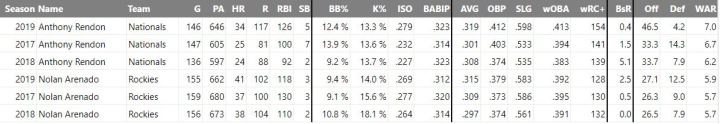

And here are their statistics over the past three seasons, broken down on a season-by-season basis.

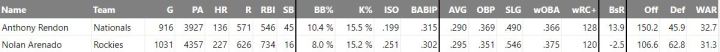

Both Arenado and Rendon debuted in 2013, and while Arenado became a full-fledged Major Leaguer by late April, Rendon was up and down and therefore Arenado has played materially more in the big leagues. Regardless, here is a side-by-side of their career numbers.

Based on recent and career history, Anthony Rendon is the superior player. He has generally drawn walks more frequently and recently, has struck out less frequently. Over the course of his career, Rendon has been a superior base runner, and while Arenado has the stronger career fielding numbers, Rendon has also been defensively stellar and the totality of his statistical profile, assuming you’re willing to acknowledge that Nolan Arenado plays his home games on the moon and should be treated as such, is superior.

But Rendon didn’t make his first All-Star Game until 2019, largely because other National League third basemen such as Arenado and Kris Bryant have commanded the headlines. Rendon has never won a Gold Glove because Nolan Arenado has won the National League Gold Glove at third base every season of their careers (Arenado has led NL third basemen in Ultimate Zone Rating in three of his seven seasons; Rendon led once). Arenado won the NL Silver Slugger award at third base in four consecutive seasons, 2015 through 2018, despite never leading the league’s hot corner occupants in Offensive Runs Above Average during that time.

Arenado is ten months and ten days younger than Anthony Rendon, which is irrelevant in terms of re-litigating their previous acclaim but doesn’t mean nothing when it comes to evaluating their futures. But Steamer projects Rendon to be the sport’s second-best third baseman in 2020, behind only Alex Bregman of the Houston Astros, while projecting Nolan Arenado to be the sport’s fifth-best, trailing Bregman, Rendon, Matt Chapman, and Jose Ramirez. Both players are, if they follow traditional aging curves, just exiting their prime–they should still be good for another few years, but they’ve probably peaked. This is usually the case with big-ticket free agents, which Anthony Rendon recently was and which Nolan Arenado, in the wake of trade rumors, essentially is.

In December, Anthony Rendon signed a free agent contract with the Los Angeles Angels for seven years and $245 million. Over the remainder of the contract Nolan Arenado signed last off-season with the Rockies, he will earn $235 million over the next seven years. In terms of average annual value, their contracts are essentially identical, though I suppose if you perceived the two as exact clones of one another, I understand preferring the slightly cheaper contract.

But there is one huge difference between the Rendon and Arenado contracts, and it isn’t money–it is opt-outs. Anthony Rendon cannot opt out of his contract, while Nolan Arenado will be permitted to opt out of his contract following the 2021 season.

As was the case with the Giancarlo Stanton contract, this opt-out limits Nolan Arenado’s upside while preserving the potential for the contract to go poorly. The Rockies, or whichever team ends up employing Nolan Arenado over the next two seasons, somewhat paradoxically want him to opt out of the contract, because that will mean he overperformed his contract and thus can command an even higher salary on the open market. If Arenado were to perform as well in 2020 and 2021 as he did in 2018 and 2019, he would likely opt out of his contract and over those two seasons, would be worth about $24 million in surplus value, by FanGraphs’s open market Wins Above Replacement estimates. But unlike other big-name players rumored to be on the trading block, such as Mookie Betts or Francisco Lindor, Arenado could conceivably remain a salary albatross well into the later stages of his career. Arenado provides similar short-term upside to Betts and Lindor (though Betts and Lindor are both projected to be better players while making less money), but his contract adds another layer of potential long-term risk.

Less than a month ago, the St. Louis Cardinals had a chance to sign Anthony Rendon and they didn’t. Given that the Cardinals are a better team than the Angels and that Rendon didn’t take a hometown discount to play in Anaheim (his hometown, Houston, is closer to St. Louis, after all), it is reasonable to assume that the Cardinals could have signed Rendon for a similar contract to what he actually got from the Angels. I’m not here to re-litigate whether the Cardinals should have signed Rendon–I’m merely noting that they were eligible to do so.

Anthony Rendon would have cost the Cardinals money and compensation draft picks, as he had the qualifying offer attached to him. Trading for Nolan Arenado would cost the Cardinals money (less, though I would argue that given the structure of the contracts, this doesn’t make the contract more desirable for the team) and potentially worthwhile future assets. Jon Morosi, who has handicapped the odds that the Rockies trade Arenado (who has a no-trade clause but may consider waiving it to find his way to a contender) as 50/50, has suggested that if the Washington Nationals, a team in the market for a third baseman following the departure of Rendon, were to pursue Arenado, it might cost them Victor Robles, a 22 year-old who just capped a 4.1 WAR rookie season by finishing in sixth in National League Rookie of the Year voting and being a finalist for the NL center field Gold Glove Award.

There isn’t a clean analogue for Robles in the Cardinals organization–he is a similar type of player to Harrison Bader, except he’s three years younger, has an additional year of club control, and isn’t coming off a down season. But considering Robles is less than a year removed from being regarded as a top prospect for the Nationals, it might be more reasonable to think Dylan Carlson or Nolan Gorman. Considering Nolan Arenado is coming off the best season of his career, it’s reasonable to assume that the Rockies are expecting actual assets for Arenado and that this isn’t purely a salary dump.

The Nolan Arenado contract is, in and of itself, fine. If the Rockies were donating him to a contending team for a non-prospect, it wouldn’t be an unreasonable thing for the contender to do. But the idea of trading actual future contributors in order to acquire a contract that is essentially what Arenado would have garnered had he reached free agency this off-season instead of just signing Anthony Rendon doesn’t make any sense. Even if you are working under the assumption that Matt Carpenter is completely cooked as a Major League third baseman, a third baseman who projects for just 0.3 fewer Wins Above Replacement next season per Steamer, Josh Donaldson, remains available on the open market. And while the older Donaldson is a less appetizing long-term option than Arenado, the entire hope in trading for Arenado is that his future under this contract only extends through 2021–otherwise, the contract is probably a disaster.

The discourse surrounding teams paying top-dollar for players has, mostly for the better, shifted in recent years from fans wanting their teams to avoiding signing players to “bad” contracts to demanding the one-percent-of-one-percent-of-one-percenters spend money because they have it. But the solution under this ideology isn’t to trade prospects for Nolan Arenado–it was to sign Anthony Rendon. Assuming Nolan Arenado is what his statistics tell us he is, trading more than spare parts for Nolan Arenado in lieu of signing Anthony Rendon doesn’t make sense under any ideology.

3 thoughts on “The cost of Nolan Arenado”